It's hard to believe that I've been gone almost a month and already "completed" one of my countries, but I could not have had a better start than I did in Japan. A country full of history, culture, and tradition, but also with its own spin on modernization, Japan taught me a lot and made me excited to see all that I will learn on this journey. But, before saying goodbye, here are three of my biggest lessons:

Mutual Respect and Trust Go A Long Way

One aspect of Japan that stuck out to me in the language, gestures, culture, and actions of the people was respect. In a conversation with fellow hostel guests (all Westerners like me I should add), it was brought up that even those who clean the subway stations were wearing a dress shirt and tie and would be greeted by subway patrons. I saw this throughout my visit; no matter who it was, where they worked, there was always a level of respect in interactions. And I couldn't help but wish, each time, that something similar existed in the United States.

It may be a naïve assumption, but I feel like this basic sense of respect for others translates to a lot of other great things I saw in Japan: very little pollution or littering, an essentially non-existent crime rate, and no chaos even during the worst of rush hour. Everything seemed almost too perfect.

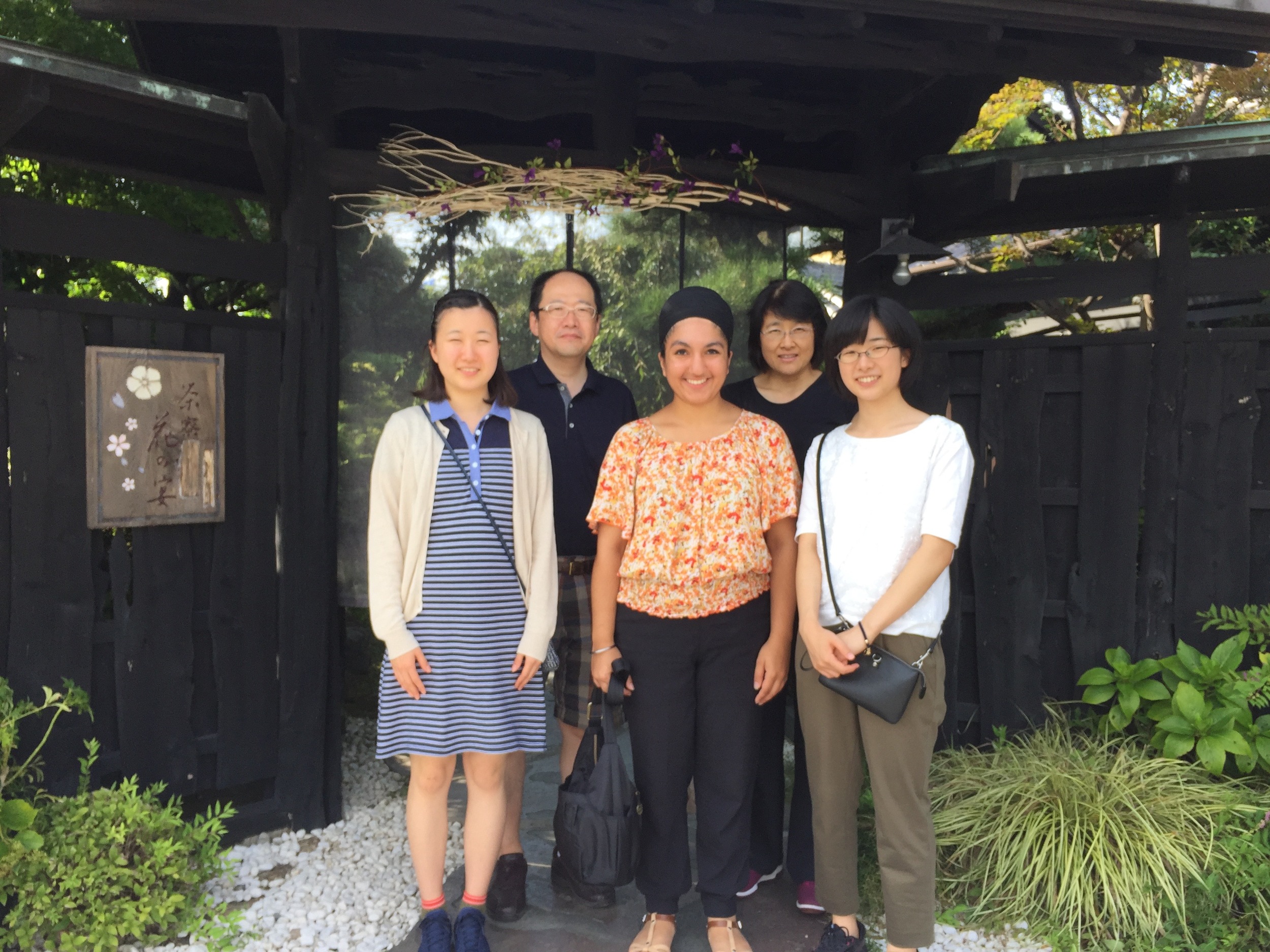

My amazing hosts for part of Japan! So thankful for their kindness.

In the U.S., I think we live too much on fear, but that doesn't seem to be the right sentiment because it's clearly not working for us. I know it was so hard for me to leave because I truly felt that I wouldn't see that level of respect, feel that level of hospitality and kindness, or get that sense of undeserved love again. But it's certainly a message I hope to carry with me and continue practicing even when I finish traveling.

The Pros and Cons of Cultural Retention

Although I remarked in earlier posts about how much I loved the retention of Japanese language and culture in certain cities and day-to-day business, downfall was the opposite: the rejection of anyone who isn't fully Japanese. Without going into the details, becoming a Japanese permanent resident or citizen is quite difficult if you are not a Japanese national (meaning not of Japanese descent). This has led to a population that is over 98% Japanese and very little understanding of anything else.

I found it interesting that while I was in Japan, a story about a biracial woman winning Miss Universe Japan was surfacing on the internet. This story seemed to capture everything I was seeing. Although the Japanese have a great pride in their culture, and have been able to retain their language and customs, this has led to rejection of those who do not fit the norm, as Miss Universe Japan discussed in the backlash she faced for being half black.

In talking with some of the Japanese friends I made, particularly the younger ones, I heard a hope for a Japan that can be more open towards other cultures. In fact, I would love to see how Japan can move towards embracing more cultures, because I think it would be a wonderful example for the U.S. Japan could demonstrate that a country can both be proud of its own culture while seeing the beauty in others. I love the small and large ways that Japan has resisted complete Westernization, but I hope that it can also move towards a more diverse Japan, so that more people can enjoy the profits of this great country.

Coffee culture has certainly made its way to Japan, particularly through young Japanese business owners who spent time abroad crafting their skills. Not that I'm complaining...

Being Alone is Important

Although not necessarily Japan specific, this first month has shown me how, at least throughout the first 22 years of my life, there have been very few moments where I am really, truly alone. Sure, even now, I'm usually surrounded by at least a few other people, or several hundreds when walking down city streets, but this has been different. The language barrier for me in Japan (and now China) have meant that it's rare for me to meet someone that I can connect with on a deep level. Even when meeting folks in hostels, or in a restaurant, the time passes quickly, and we usually have a day or two together at most before our paths split. This leaves little time to get beyond pleasantries and sharing travel stories from the past few days.

Human connection is important, and I've come to cherish my family and friends even more already, but I'm also seeing the immense value in building a relationship with myself. This time will allow me to better understand what values are the ones that stick throughout all environments and cultures and which ones I may need to outgrow. It will allow me shift my beliefs and knowledge beyond what I learned in school and through both an Indian and American upbringing, and create a philosophy that is truly all my own. And then, when I do return home, I will have the knowledge and power that what I want is truly what I want, because I had the time to figure it out for myself.

Unreal sunset as I flew out of Osaka's airport (which, by the way, is an island they constructed to have enough room for an airport). Best way to say bye to Japan!